View News

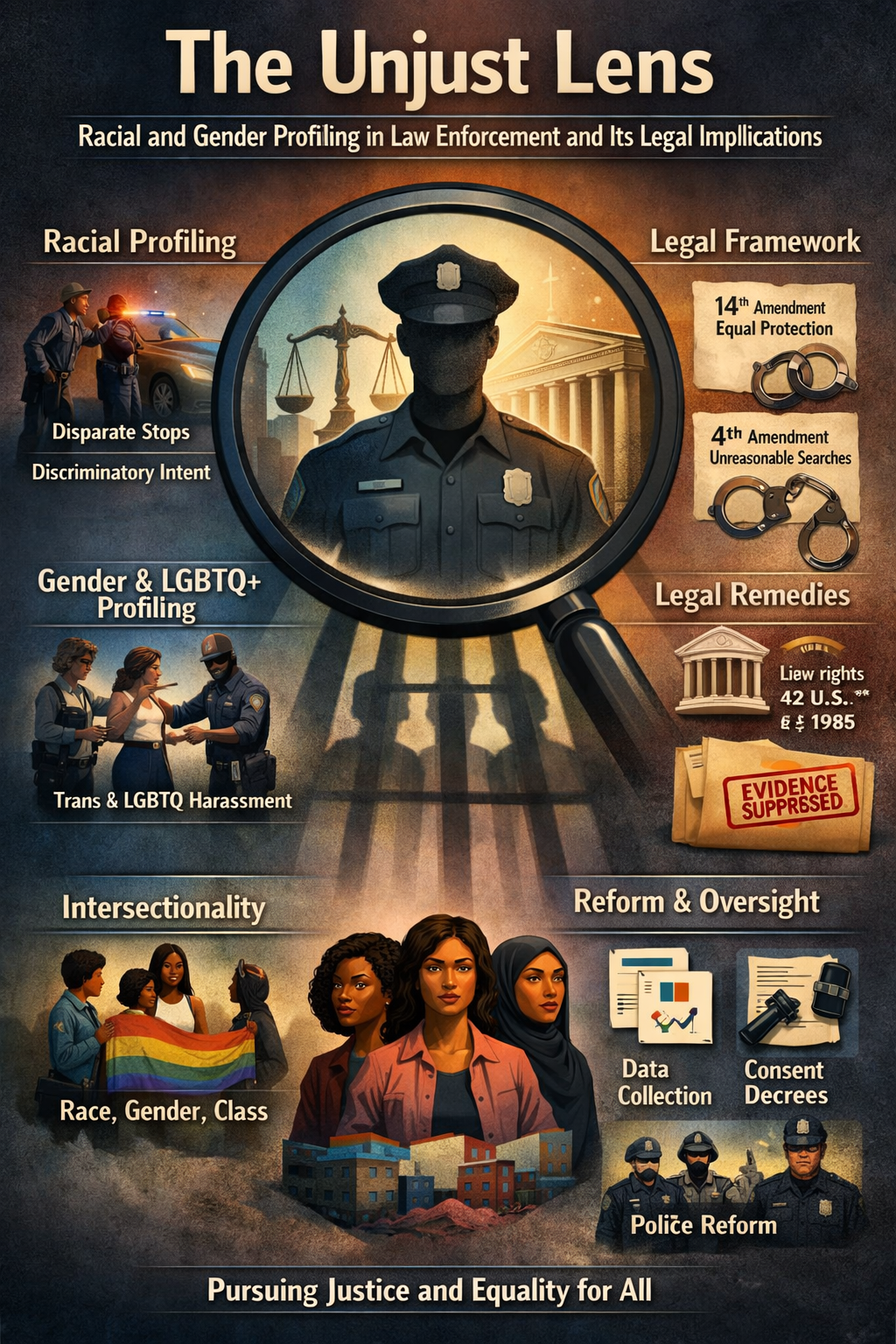

The Unjust Lens: Racial and Gender Profiling in Law Enforcement and Its Legal Implications

The Unjust Lens: Racial and Gender Profiling in Law Enforcement and Its Legal Implications

~Sura Anjana Srimayi

Introduction

Racial and gender profiling in law enforcement is a practice that undermines justice, equality, and the rule of law. It occurs when individuals are singled out for suspicion or enforcement based on attributes such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, sexual orientation, or socio-economic status rather than any evidence of wrongdoing. In the United States, Black, Latino, Indigenous, and other marginalized communities are disproportionately affected by profiling, yet the problem extends beyond race. Gender, sexual orientation, and class intersect with racial identity to produce compounded discrimination. This layered impact, known as intersectionality, highlights the unique vulnerabilities faced by those subject to multiple forms of bias. Studies by the Bureau of Justice Statistics have shown that Black drivers are approximately twenty to thirty percent more likely to be stopped by police than white drivers, despite similar rates of traffic violations.

Legal Framework and Constitutional Challenge

The U.S. Constitution provides the primary mechanism to challenge discriminatory policing practices. The Fourteenth Amendment, particularly its Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses, and the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures are central to addressing profiling.

Under the Equal Protection Clause, no state may deny any person equal protection under the law. Legal challenges based on racial or gender profiling generally require proof of two elements. The first is disparate impact, which demonstrates that a practice disproportionately affects a specific racial or social group. For example, when traffic stops consistently target minority neighborhoods without evidence of higher crime rates, this can indicate discriminatory effect. The second element is discriminatory intent, which requires demonstrating that the unequal impact is deliberate. Establishing intent is legally challenging and often relies on circumstantial evidence, including patterns in department policy, prior incidents, training materials, or statements by law enforcement personnel. The landmark Supreme Court case Washington v. Davis in 1976 established that showing disparate impact alone is insufficient; plaintiffs must also demonstrate discriminatory intent to prove a violation of the Equal Protection Clause.

The Fourth Amendment protects individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures. Profiling frequently leads to unlawful stops or searches. Courts evaluate the legality of these actions based on whether there was reasonable suspicion for stops or probable cause for searches and arrests. When suspicion arises from racial or gender prejudice rather than objective, observable behavior, any evidence obtained may be suppressed under the Exclusionary Rule. The New York City Stop-and-Frisk program, which operated extensively from 2004 to 2013, exemplifies this issue. Over eighty percent of stops targeted Black and Latino individuals, yet most of those stopped were innocent, highlighting the unconstitutional nature of profiling.

Legal Consequences and Remedies

Victims of profiling have access to multiple legal remedies. Evidence obtained through unconstitutional searches can be suppressed in court. Civil rights litigation under Section 1983 of the U.S. Code allows individuals to sue police officers or departments for violations of constitutional rights. Remedies may include monetary compensation, injunctive relief, or systemic policy changes aimed at preventing further violations.

Gender and Intersectional Dimensions of Profiling

Profiling rarely occurs on a single axis of identity. Gender, sexual orientation, and socio-economic status intersect with race to create unique vulnerabilities. Women of color often experience profiling differently than men. In the context of drug law enforcement, women from marginalized communities may be presumed complicit in male relatives’ activities and subjected to invasive searches. Single mothers of color frequently face heightened scrutiny from social services and law enforcement under the guise of welfare fraud prevention or child welfare monitoring, reflecting racialized stereotypes regarding poverty and family structures. Even in traffic enforcement, women of color who are stopped may encounter intrusive questioning and gender-based dehumanization, despite lower overall stop rates compared to men of color. Research by the National Institute of Justice demonstrates that Black women are twice as likely to be searched during traffic stops compared to white women when accounting for violations.

Profiling also extends to LGBTQ+ individuals. Transgender women of color, for instance, experience high rates of stops, searches, and harassment based on perceived involvement in sex work or gender nonconformity. Homeless LGBTQ+ youth, particularly racial minorities, report frequent encounters with law enforcement that include harassment, abuse, or searches without probable cause. These practices directly challenge constitutional protections under the Equal Protection Clause and highlight the compounded vulnerability created by the intersection of race, gender identity, and socio-economic status.

Policy, Data, and the Path to Legal Reform

Addressing profiling effectively requires combining legal strategies with data-driven accountability. Mandatory collection and analysis of policing data, including traffic stops, frisks, and searches broken down by race, gender, and outcome, can provide statistical evidence of disparate impact. Such evidence allows courts to infer systemic bias without requiring proof of explicit intent. Several states, including California and New York, have implemented legislation mandating this type of data collection as a prerequisite for policy evaluation and reform.

When profiling is systemic, federal courts may enforce Consent Decrees, legally binding settlements between government agencies and police departments. Consent Decrees require reforms in policies and training, implementation of accountability mechanisms such as body-worn cameras, and ongoing court supervision to prevent unconstitutional practices. Between 2001 and 2020, the U.S. Department of Justice entered into over twenty Consent Decrees with police departments found to engage in unconstitutional practices, including profiling and excessive use of force. At the state and municipal level, legislation explicitly banning racial, gender, and religious profiling provides additional legal protections and remedies for victims.

Conclusion

Racial and gender profiling represents a systemic failure in law enforcement that undermines the constitutional guarantees of equality and due process. Although legal remedies are often limited by the challenge of proving discriminatory intent, civil rights litigation, disaggregated data collection, and federal oversight mechanisms such as Consent Decrees are gradually improving accountability. Understanding intersectionality is essential, as many individuals face multiple, overlapping vulnerabilities related to race, gender, sexual orientation, and socio-economic status. Legal reform must recognize these layers of discrimination to ensure that policing truly upholds the constitutional promise of equal protection for all individuals, regardless of who they are or how they appear. Eliminating profiling is not solely a legal issue; it is a societal imperative requiring transparent policing, unbiased enforcement, and vigilant oversight.

"Unlock the Potential of Legal Expertise with LegalMantra.net - Your Trusted Legal Consultancy Partner”

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to avoid errors or omissions in this material in spite of this, errors may creep in. Any mistake, error or discrepancy noted may be brought to our notice which shall be taken care of in the next edition In no event the author shall be liable for any direct indirect, special or incidental damage resulting from or arising out of or in connection with the use of this information Many sources have been considered including Newspapers, Journals, Bare Acts, Case Materials , Charted Secretary, Research Papers etc

LegalMantra.net team